Earlier this week, I was lucky enough to catch Dave Chappelle live in concert in Dayton and in a sobering moment he commented that America is a heartbreak factory; live here long enough and you are bound to encounter heartbreak. If that’s true, the blues is one of the factory’s oldest products, one of the few true American products being made. Like most products, it has benefited from being retooled by outside influences.

In the ‘60s, America turned its back on the blues, then England (The Rolling Stones, Cream, Led Zeppelin) reenergized it and sold it back to us in spades. As Buddy Guy once said, “But that’s America, man. Nobody knows what they got.” Punk and disco came, and we let the blues slip away again. We continue to cycle in and out of the arrangement. Recently, England got distracted by royal babies, Brexit and Harry Styles’ cheekbones, so we took the blues back and buffed it up again (Jack White, The Black Keys, more recently Greta Van Fleet).

Somewhere in the U.K. someone’s on deck ready for their turn when our attention drifts to EDM or hip-hop or Kardashian babies; enjoy it while we can and while we’re still lucky enough to have one of the originals around. As with any factory, some folks spend their life on the line working hard behind the scenes, some cut loose and move on to the new pursuits and some folks love it so much they keep working way past the time they should be enjoying their retirement.

At 82, Buddy Guy is long past retirement age and still going strong. At times the blues has been in danger of becoming so normalized that it could be safe background music for your local rib fest-the twelve-bar blues patterns so familiar that it’s easy to miss the emotion and darkness underneath. It’s rare when we can sit still for a bit, focus and experience it undiluted from one of the original masters. It’s a bit like drinking Diet Coke for years, then catching hold of one of those Mexican Cokes they make with real sugar. It’s the real thing indeed.

Context is key. To understand Buddy now, it’s helpful to look back a bit. As a kid, music was magical to Buddy Guy. In a place where running water, indoor plumbing and electricity weren’t commonplace, he’d sit enraptured by itinerant guitar players or the family battery powered radio after long days of picking Louisiana cotton. He’d spend nights listening to a mix of black and white music, itching to play so badly that he used anything he could get his hands on as a proxy -a broom, rubber bands, a button on a string or wires pulled out of the window screens and strung to tin cans. When he finally saw a live concert, his path was clear, and it wasn’t long before he got his first real guitar and got on stage. He was self-taught and crafted his style from bits of guitarists he loved and his own unique passion to get out what he heard in his head. After trying to make it in Baton Rouge and working odd jobs in between gigs, he realized he had to move on. Buddy headed to Chicago in 1957 because that was where the action was. The electric blues were flourishing, and he wanted in on the action. In a town of big shoulders and great guitar gunslingers, he knew the only way to stand out was to burn even brighter and give the crowds something nobody else could. So, he’d smack the strings with a handkerchief or pick the strings with his teeth and leave his axe on the ground, growling in a wash of reverb. One of his favorite tricks was to use a 150-foot long cord to start playing outside and come in roaring through the audience. Anything to get attention. He worked hard, cutting heads for a bottle of whiskey on Sundays at a rough and tumble southside Chicago joint. His efforts got him gigs and he worked on sessions with legends like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. He and Muddy became fast friends and that made it a bit easier to endure Leonard Chess (head of Chess Records) and his refusal to let him cut loose on records.

Buddy struggled to balance the duality of days as a session man, playing it clean and staying within the structure of other people’s songs, with nights tearing up Chicago clubs with his scalding, frenetic blues. Soon, the rest of the world took notice. Buddy joked that his own neighbor didn’t even know his name, but English artists like Eric Clapton and The Rolling Stones were vocal supporters. He embraced flawed feedback and fuzz as a beautiful extension of his passion, a decade before Hendrix. When he was asked about copying Jimi, he said, ‘Who’s Hendrix?” Folks had it backwards, but Jimi acknowledged his debt to Buddy. Someone recently unearthed a jaw-dropping video on YouTube from 1968 where an awestruck Jimi Hendrix is jamming with Buddy Guy. It’s staggering to think what music could have been created if Jimi was still around.

Over sixty years later, Buddy Guy is as passionate as ever about keeping the blues alive. He talked to his mentor Muddy Waters the day before he died, and Muddy made him promise to not let the blues die on him. Buddy’s still making good on that promise. His most recent studio album (2018) is titled The Blues is Alive and Well. As confident as that title is, it’s sad to think that Buddy Guy is one of the last of an era; maybe thelast. The last link in a long chain that stretches from the cotton fields of Louisiana to the rough streets of Chicago to the beautiful shores of Lake Erie and The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He ties together the legends he came up with (Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker) to the next wave of folks Buddy influenced (The Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Billie Gibbons, Stevie Ray Vaughn) to current artists that revere him (Kenny Wayne Shepherd, Gary Clark. Jr.) and beyond. Jimi Hendrix has been gone almost fifty years. Stevie Ray passed almost thirty years ago. Astonishingly, Buddy survived them both and has endured massive cultural shifts and he soldiers on.

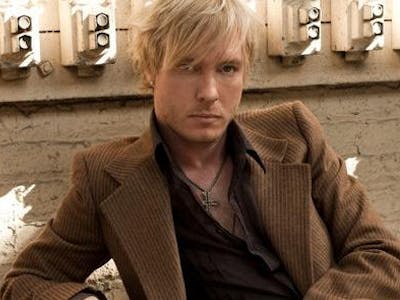

Opening act Kenny Wayne Shepherd beautifully set the stage for Buddy. Shepherd just turned 42 this week, but he’s already survived almost twenty-five years in the record business. His influence and admiration of Buddy is clear, and he plays with the same sincerity and passion.

His band’s sound hews more to the southern or Texas rock-blues (think Stevie Ray Vaughn and The Allman Brothers) and it’s a great, crunchy crossbreed. Whether it was ripping through their own songs (“Woman Like You”) or covers (Buffalo Springfield’s “Mr. Soul”, Gladys Night’s “I’ve Got to Use My Imagination”), the band put their own stamp on things. The horn section (saxophone and trumpet) was a great addition and gave a Stonesy Exile on Main Streetvibe to the songs. The Stevie Ray Vaughn influence was clear in Shepherd’s playing, but it was shocking to hear hints of Eddie Hazel (from Parliament-Funkadelic) in one of his long solos. And, at times, when the sound thickened the band had echoes of Soundgarden. The whole set was an apt retooling of the blues sound for people that have grown up in the rock and alternative era. The enthusiastic crowd pulled them back for two encores – their own “Blue on Black” and Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)”. I saw Shepherd do this song in 1998 when he opened for Bob Dylan. He was good then, he’s great now. His talent has flourished beautifully and he absolutely crushed the challenging song.

After a brief intermission, Buddy took the stage, looking hale and dapper in gray overalls and white cap. He started playing as the band (keys, guitar, bass and drums) vamped behind him. A huge grin crossed his face and he launched into his signature song “Damn Right ,I’ve Got the Blues” He immediately flexed his muscles, launching into long solos, taking his hands off the guitar and bumping it with his hips to make it squawk and extending the song so long he had to ask afterwards if it was toolong.

He joked that he was confused where he was because when he was in his hotel it was Ohio, then they were heading to the venue and it said Kentucky, then it said Ohio again. He laughed because he said he hadn’t even been drinking but that might drive him to it. He smiled again as he promised to “play something so funky you can smell it” and kicked the band into Willie Dixon’s “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man.” Buddy was clearly having fun -playing one handed, turning the guitar around so the strings pressed against his chest and rubbing it around to scratch the strings or playing with his elbow. “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” flowed seamlessly into Muddy Waters’ “She’s 19 Years Old” and then into Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper to Keep Her.”

Buddy took a pause and fired off the start of Willie Dixon’s “I Just Want to Make Love to You”. As the band swung in and the Hammond organ filled the space between guitars, Buddy stopped and let the crowd sing the chorus. He looked out mischievously and said, “Oh sh*t, I like that!”

He took a minute and bemoaned the fact that you don’t hear that kind of blues on the radio anymore. When he was in Africa, he was asked if he could play anything besides the blues. He confessed that was all he knew, but he could try something. He glanced back slyly at the band and started riffing Jimi Hendrix’s “Foxy Lady,” letting it bleed into “Purple Haze.”

As the night air cooled, the rumble of storms threatened in the distance. Buddy said that before the show, he wasn’t sure how the weather would affect things, but he had a song we could relate to. As unwelcome as more rain is after this week’s deluge, his beautiful version of John Hiatt’s “Feels Like Rain” was simple and moving. As he came to the chorus he stopped and caught the crowd a bit by surprise, expecting them to jump in. He mock-growled at the blunted response and chided them, “I didn’t come here for you to f*ck up my song.” He said they had to imagine something they wanted to hold onto and then hold onto the phrase longer. He sang it again and told the crowd to try again. Given a second chance, they nailed it and he seemed pleased. He admitted, “I know I can’t please everybody, but I’ll give you every f*cking thing I’ve got.”

And he proved that over and over, pulling out all his showman’s tricks – laying his guitar flat and whacking it with a drumstick, letting it hum with reverb, smacking it with a towel, tapping out the intro of “Sunshine of Your Love” with a drumstick, then flipping the guitar behind his back and picking out the same intro, then sliding the guitar down and using his bottom to scratch out the intro a third time, goofing around. He was excited and seemed to want to play multiple songs at once, picking out The Rolling Stones’ “Miss You” or Al Green’s “Take Me to the River,” or exhorting the crowd to sing along to Johnnie Taylor’s “Who’s Making Love.” The crowd could barely keep up with him.

In between songs, he charmed the crowd and said that twenty-five years ago someone asked why he hadn’t visited Cincinnati before. People told him had to come and he finally did. His affection was clear when he warmly said, “I finally got back here, and I love you more than ever.” When he asked the audience to name the greatest guitar players, a babble of voices overlapped. One man kept yelling out “Howlin’ Wolf”. Buddy calmly corrected him, “Sir, Howlin’ Wolf was a harmonica player.” When the man started to protest Buddy said (non-threateningly, clearly in good nature), “If you’d shut the f*ck up, I’m trying to educate you” and said if the man knew more than he did, he could come up on stage and Buddy would trade places with him. Then he grabbed a pick and said this was the greatest guitar player he ever heard and lit into B.B. King’s “Sweet Sixteen.” He admitted that John Lee Hooker was up there as well and did a bit of his song “Boom Boom” as follow up.

All that was warmup for his greatest trick, maybe his oldest one. As the band started into “Someone Else is Slippin’ In,” Buddy grabbed a microphone and started walking off the stage into the crowd. He doesn’t need a long amp cord anymore; his wireless rig lets him stroll off stage and roam freely. The crowd buzzed as he worked his way through the pavilion, playing guitar and singing as he made his way up the aisles. He paused in the back of the venue and sang as hundreds of smartphones were out as people processed the thrill of being inches away from a living legend. Old trick, still works. Everybody loves a legend.

Buddy got back on stage and apologized to the folks trying to shake his hand as he went by. “That’s why I’m not a politician – I can’t shake your hand and play guitar at the same time.” He settled back in and expressed his admiration for Eric Clapton and payed homage to him by playing one of his songs (“Strange Brew”) from when he was in “The Cream” (sic.). It was a joy to see him guide his band with a subtle finger held at his side, walking them along as he expressed his love of expensive liquor (“Cognac”) or acknowledged more old masters (Slim Harpo’s “King Bee”).

As the evening came to a close, Buddy marveled that at one time he had to learn all the songs on the jukebox to make a living. He said, “Can you imagine, I had to learn Marvin Gaye?” then he started singing a sweet version of “Ain’t That Peculiar” before going into one final jam. Buddy set down his guitar, grabbed handfuls of guitar picks and started throwing them out into the delighted crowd. He exited, the band kept playing and eventually took their bows. Despite a strong crowd response, there was no encore. Then again, his whole set was encore level. He didn’t have anything left to prove.

Kenny Wayne Shepherd is forty years younger than Buddy Guy and it’s reassuring to think of Shepherd playing out under the stars in 2059 and continuing to carry the torch for the blues. And somewhere, some precocious kid that hasn’t even been born yet will pick up a broom or rubber bands or bang away on that decade’s version of Garageband and start making the same primal noise. Keep the factory open until the next century, maybe open for Kenny Wayne and inspire the next generation. Buddy once said, “If you don’t think you have the blues, just keep living.” The corollary to that is- as long as there’s life, the blues will never die. Man, Muddy would be proud.